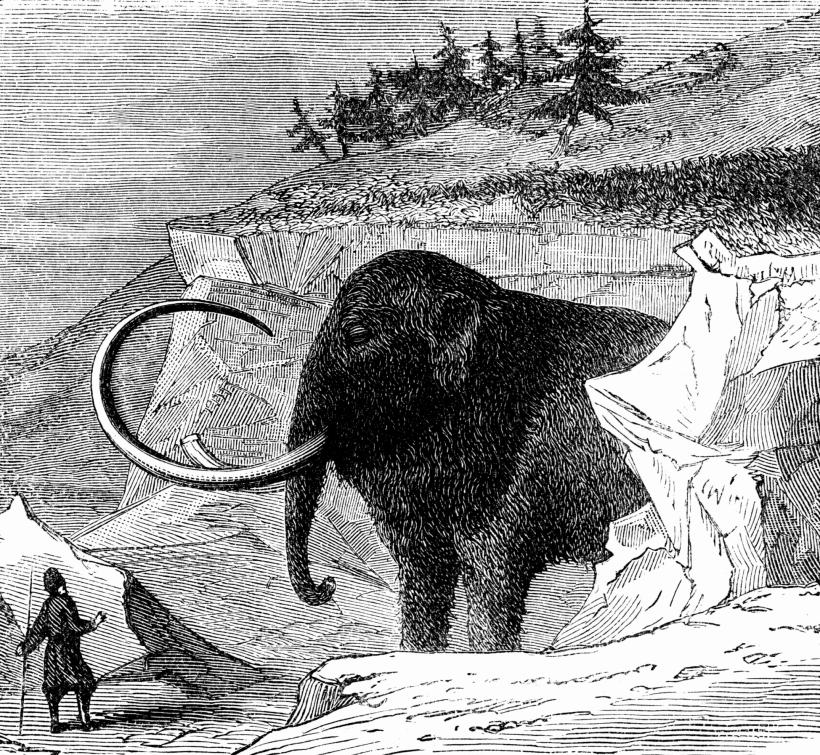

Next month, scientists will gather in Dordogne, France to mark the 150th anniversary of a landmark discovery in human history. It’s big and tusky with fur all over: The Madeleine mammoth. The wooly creature bequeathed its ivory to a local band of Homo sapiens for their artistic expression, and the resulting engraved ivory rocked the world of 19th century natural history. It proved that man had lived alongside these prehistoric creatures, and thus showed that mankind was much older than people of the day imagined.

Back to the Reindeer Age

You’ve probably heard of the famous—and incredibly incorrect—timeline of 17th century British Archbishop James Ussher, who pegged the earth as a spring-chicken of just 6,000 years old (still an estimate much-beloved by modern young-earth creationist). But in the 18th and 19th centuries, evidence began mounting that the dear bishop had underestimated the planet’s longevity.

In the 1840s for example, scientists began to realize that rock deposits found in the Alps must have been leftovers from glaciers that had covered much of Europe. Yes, inhabitants of the Victorian age were beginning to wrap their heads around the idea of an ice age. Though at the time scientists dubbed the long-ago period as the “Reindeer Age”—literally because they began digging up reindeer remains in the warm expanses of southern Europe, which further signaled continent’s former frostiness.

Another critical find of the day: scientists found human artifacts mixed with bones of extinct animals in several European riverbanks. This of course indicated humans were alive during this icy Reindeer Age. Naysayers disagreed, arguing flood waters had simply mixed the artifacts over the years.

Would there ever be definitive evidence of human co-existence with ancient animals?!?

Excavation at La Madeleine

Fast forward to one fateful day in May of 1864.

A work team was carrying out orders to partially excavate a site at at Abri de la Madeleine—a prehistoric shelter for various creatures located under an overhanging cliff. By a stroke of luck, two of the leading paleontologists of the day just happened to be on site, and some fragmented pieces workmen were carrying out caught their attention. Closer inspection indicated the bits came from a single item.

Once glued together, the La Madeleine pieces formed a 9-inch-long chunk of mammoth ivory. But the exciting part? One side of the tusk was engraved with drawings of a mammoth. And how could people have carved depictions of the creatures unless they (gasp!) actually saw them in the flesh?

By George, they’d done it! They had found what the excavation had been looking for: proof that humans once shared the Earth with these massive, long-extinct beasts. Suddenly, the history of man just got a whole lot longer.

Since that day, the La Madeleine site has delivered a whole slew of ancient human tools, remains from mammoths, woolly rhinos, extinct wolverines, (now less exciting) reindeer, and more fossil carvings from between 12,000 and 16,000 years ago which added more evidence to that initial mammoth carving.

Party Time

So we hope researchers live it up at next month’s commemoration—on behalf of the paleontologists and work team that made the finding, and of the mammoth and humans who created an interspecial time capsule of their ancient co-existence. And modern scientists shouldn’t forget to toast the reindeer—the creatures got overshadowed by the whole wooly mammoth business. But hey, they dutifully did their part to represent the icy Magdalenian era.

Image: Thinkstock